I have been “doing my research” (wandering around the interwebs…), as people so often say these days, on what would be the best cost solution to provide electricity in an extended grid-down situation. I don’t want to spend the money it would cost to provide enough electricity to keep the house running as if the grid were still up – that would cost way more than $10,000 and isn’t a condition we have faced more than once. I live in the middle of the city of Saint Louis, MO, USA and our grid has been, and is likely to remain, pretty reliable, but I expect more outages in the future. So, what’s big enough to run a refrigerator, power our cell phones, some lights and maybe a fan? The best conclusion I can come up with is about 5kWhs of battery storage capability, with a 3kW inverter. I know a fair amount about solar, but not so much about batteries.

Will Prowse is a YouTube content creator who seems rather informed, though it’s not like he’s a professionally educated electrical engineer or an electrician. I can tell he knows a lot more about batteries than I do. I am going to trust his judgement and put together the system he recommends, which should cost me about $2,300 USD before solar panels, which will probably add $800 – $1,000 USD. It’s mobile, if we ever want that capability, it should cover more than just cell phones and LED lights and could provide a minimum level of comfort if the grid goes down for an extended period.

We already own two good sized battery packs – we have electric vehicles, and could draw electricity from them for a bit. The bigger car battery could probably run our large kitchen refrigerator for most of a day, but not a lot else. Of course, you can’t both use the power in the batteries for the house and drive at the same time, so that would have to be thought through in the case of a multi-day grid-down situation.

As you can see in the snippet above (picked up from our utility’s website), during the heat of summer, our house uses as much as 130 kWhs a day of grid-supplied electricity. Yes, that’s a lot; most likely about 75% of that is for central air conditioning. There is no way I want to pay for enough battery backup to supply that seamlessly, even without central air conditioning – just too much money. So the piddly little 5kWh backup system will only provide a minimum amount of our needs. Essentially, the grid goes down and we’re suddenly camping.

I have also looked into buying a used Tesla car battery – a ’21 had gotten into an accident after only using that battery for 3000 miles. I could have gotten that battery delivered to my house for about $4,000 USD, but I didn’t feel confident in my ability to build a backup system using a salvaged Tesla battery, so I stuck with the technically simpler option – the one demo’d by Will Prowse.

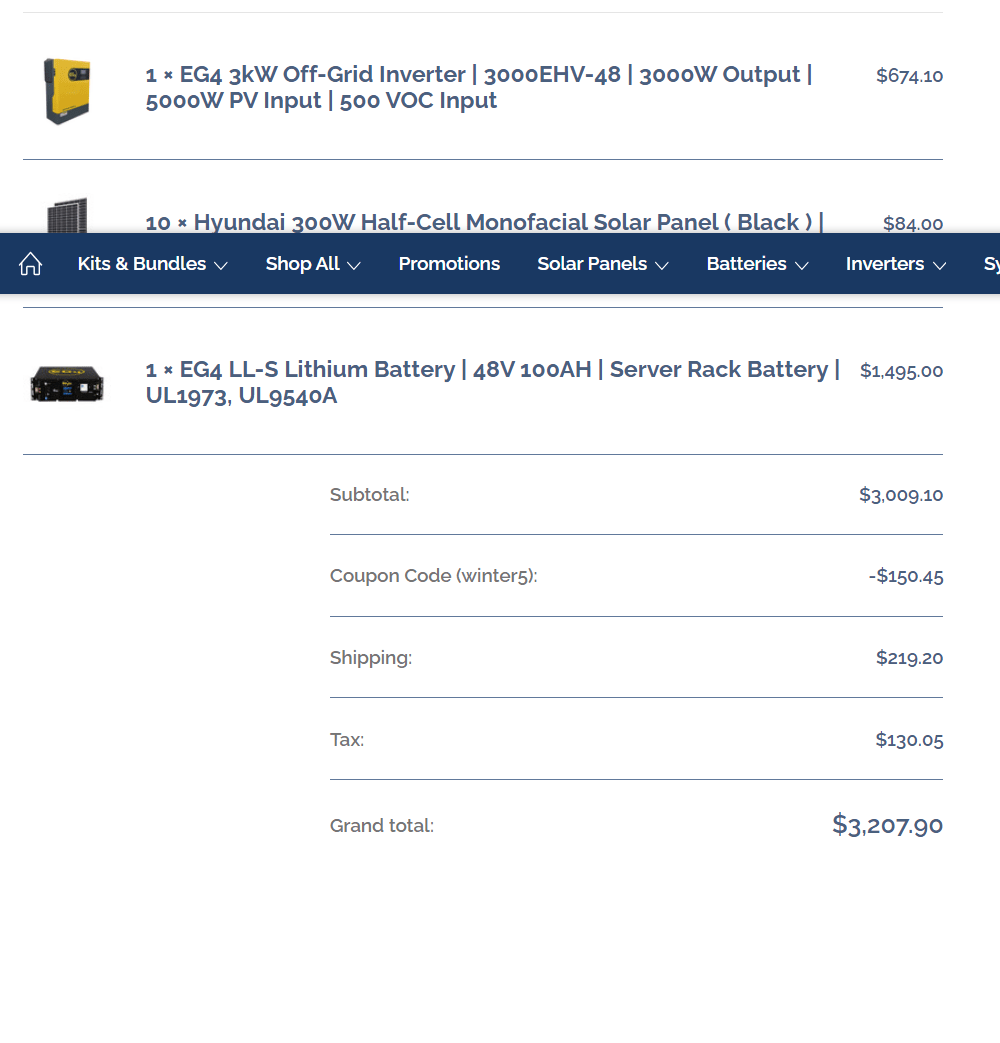

I purchased my parts – a 3kW watt all-in-one type inverter, a 5kW server rack battery and ten 300 watt solar panels on 12/14/2023 from Signature Solar, and you can see the prices below. I was told that I needed to order a minimum of 10 solar panels, which was a reasonable fit for this system, so I did, just for convenience. I could/should have shopped a little more for solar panels, but this was good enough. I think Will Prowse recommends about 1200 watts of solar panel power as input for this system, but the 3kW generated by this string of ten 300 watt panels shouldn’t be too much for the 500 volt limit of the inverter.

It was a tough decision comparing my various options, but I think this is good enough to meet our needs for now and will have the advantage of lowering our electric bills a bit. BTW, this will be off-grid, not grid-tied. We’ll be powering some of our needs (notably our large kitchen refrigerator) from this system instead of the grid which will decrease the amount of electricity we’re picking up from the grid. The cost of grid-supplied electricity has risen substantially in the last ten years and I expect that will continue. $3,207.90 would buy a whole lot of grid-supplied electricity; the benefit of buying and using this system would be that it would help stabilize our energy costs during the life of this system and be very valuable in an extended grid-down situation. This isn’t the ideal situation for everybody, but it meets our needs.

What do you think? Please let me know if you have any questions or suggestions. And thanks for reading this far!